John Roseboro

| John Roseboro | |

|---|---|

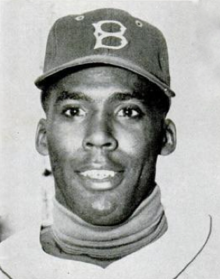

Roseboro in 1957 | |

| Catcher | |

| Born: May 13, 1933 Ashland, Ohio, U.S. | |

| Died: August 16, 2002 (aged 69) Los Angeles, California, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| June 14, 1957, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 11, 1970, for the Washington Senators | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .249 |

| Home runs | 104 |

| Runs batted in | 548 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

John Junior Roseboro (May 13, 1933 – August 16, 2002) was an American professional baseball player and coach. He played as a catcher in Major League Baseball from 1957 until 1970, most prominently as a member of the Los Angeles Dodgers. A four-time All-Star player, Roseboro is considered one of the best defensive catchers of the 1960s, winning two Gold Glove Awards. He was the Dodgers' starting catcher in four World Series with the Dodgers winning three of those.[1]

Roseboro is known for his role in one of the most violent incidents in baseball history, when San Francisco Giants pitcher Juan Marichal struck him in the head with a bat during a game between the rival Dodgers and the Giants on August 22, 1965.[2]

Early life

[edit]Roseboro was born in Ashland, Ohio to Cecil Geraldine (née Lowery) and John Roseboro Sr. on May 13, 1933. He had a younger brother named Jim who played football as a halfback at Ohio State University.[3]

He attended Ashland High School where he played both baseball and football. He was the catcher on the baseball team but, preferred playing halfback for the football team and won a football scholarship to attend Central State University.[4]

During this time, Roseboro was spotted by Dodgers scout Hugh Alexander working out with the baseball team (due to poor grades, Roseboro was ineligible to play for the baseball team). Alexander liked what he saw and invited him to try out for the Brooklyn Dodgers when they came to play in Cincinnati.[5]

Baseball career

[edit]Minor league years

[edit]Roseboro was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers as an amateur free agent before the 1952 season and, began his professional baseball career with the Class-D Sheboygan Indians of the Wisconsin State League.[6] He posted a .365 batting average with Sheboygan in 1952 to finish second in the league batting championship.[7]

After Roseboro was promoted to the Class-C Great Falls Electrics of the Pioneer League in 1953, he was drafted into the United States Army which forced him to miss the remainder of the 1953 season and the whole of the 1954 season. Upon completing his military service in 1955, he played in the Class-B Cedar Rapids Raiders of the Illinois–Indiana–Iowa League and the Class-A Pueblo Dodgers of the Western League.[6]

Before the 1956 season, he was promoted to the Triple-A Montreal Royals of the International League. In June 1957, after five years in the minor leagues and shortly after his 24th birthday, he was promoted to the major leagues.[8]

Major League career

[edit]Campanella's heir apparent

[edit]During his first season in the major leagues, Roseboro served as backup catcher for the Dodgers' perennial All-Star catcher Roy Campanella and was being groomed to be Campanella's replacement. However, in January 1958, he was promoted to the starting catcher's position ahead of schedule when Campanella was badly injured in an automobile accident that left him paralyzed from the shoulders down and ended his athletic career.[9][10]

In his first full season, with the team having moved to Los Angeles, Roseboro hit for a .271 batting average, along with 14 home runs and 43 runs batted in.[11] He was also named as a reserve player for the National League in the 1958 All-Star Game.[12] In 1959, Roseboro led the league's catchers in putouts and in baserunners caught stealing, helping the Dodgers win the National League pennant.[13][14] The Dodgers went on to win the 1959 World Series, defeating the Chicago White Sox in six games.[15]

After having a below par season in 1960, Roseboro rebounded in 1961 posting career highs with 18 home runs and 59 runs batted in.[11] He also led the National League catchers in putouts and double plays and finished second in fielding percentage and in assists to earn his first Gold Glove Award when the Dodgers finished the season in second place behind the Cincinnati Reds.[16][17][18] He also earned his second All-Star team berth as a reserve player in the 1961 All-Star Game.[19]

During spring training 1962, Roseboro was amongst the group of black Dodger players, along with Tommy Davis, Maury Wills, Jim Gilliam, and Willie Davis, who approached Peter O'Malley, son of the Dodgers' owner, and demanded that segregation come to an end at Dodgertown. Unlike the spring training facilities for players, the facilities for spectators, including the seating in Holman Stadium, were still racially segregated. Their demands were met and all signs in the stadium marked "Colored" were removed. Roseboro and Davis both later encouraged black spectators sitting the formerly segregated seats to sit wherever they wanted to.[20]

Roseboro earned his third All-Star berth, as a reserve in the 1962 All-Star Game.[21] The Dodgers battled the San Francisco Giants in a tight pennant race during the 1962 season, with the two teams ending the season tied for first place and meeting in the 1962 National League tie-breaker series. The Giants won the three-game series to clinch the National League championship.[22][23]

In 1963, Roseboro helped guide the Dodgers' pitching staff to a league leading 2.85 earned run average as, the team clinched the National League pennant by six games over the St. Louis Cardinals.[24][25] Roseboro made his presence felt in the 1963 World Series against the New York Yankees when he hit a three-run home run off Whitey Ford to win the first game of the series. The Dodgers went on to win the series by defeating the Yankees in four straight games.[26] The Dodgers dropped to seventh place in the 1964 season, however Roseboro hit for a career high .287 batting average and led the league's catchers with a 60.4% caught stealing percentage, the ninth highest season percentage in major league history.[27][28]

Roseboro-Marichal incident

[edit]Roseboro was involved in a major altercation with Juan Marichal during a game between the Dodgers and San Francisco Giants at Candlestick Park on August 22, 1965. The Giants and the Dodgers had nurtured a heated rivalry with each other dating back to their days together in New York City.[29] As the 1965 season neared its climax, the Dodgers were involved in a tight pennant race, entering the game leading the Milwaukee Braves by half a game and the Giants by one and a half games.[30] The incident occurred in the aftermath of the Watts riots near Roseboro's Los Angeles home and while the Dominican Civil War raged in Marichal's home country so emotions were raw.[31]

Maury Wills led off the game with a bunt single off Marichal, and eventually scored a run when Ron Fairly hit a double. Marichal, a fierce competitor, viewed the bunt as a cheap way to get on base and took umbrage with Wills.[31] When Wills came up to bat in the second inning, Marichal threw a pitch directly at Wills, sending him sprawling to the ground. Willie Mays then led off the bottom of the second inning for the Giants and Dodgers' pitcher Sandy Koufax threw a pitch over Mays' head as a token form of retaliation.[31] In the top of the third inning with two outs, Marichal threw a fastball that came close to hitting Fairly, prompting him to dive to the ground.[31] Marichal's act angered the Dodgers sitting in the dugout and home plate umpire Shag Crawford then warned both teams that any further retaliations would not be tolerated.[31]

Marichal came up to bat in the third inning expecting Koufax to take further retaliation against him. Instead, he was startled when Roseboro's return throw to Koufax after the second pitch either brushed his ear or came close enough for him to feel the breeze off the ball.[32] When Marichal confronted Roseboro about the proximity of his throw, Roseboro came out of his crouch with his fists clenched.[30] Marichal afterwards stated that he thought Roseboro was about to attack him and raised his bat, striking Roseboro at least twice over the head with it, opening a two-inch gash that sent blood flowing down the catcher's face and required 14 stitches. Koufax raced in from the mound attempting to separate them and was joined by the umpires, players and coaches from both teams.[30]

A 14-minute brawl ensued on the field before Koufax, Mays and other peacemakers restored order. Marichal was ejected from the game. Afterwards, National League president Warren Giles suspended him for eight games (two starts), fined him a then-NL record $1,750 (equivalent to $17,000 in 2023), and forbade him from traveling to Dodger Stadium for the final, key two-game series of the season. Roseboro filed a $110,000 damage suit against Marichal one week after the incident but eventually settled out of court for $7,500.[30]

Years later, in his memoirs, Roseboro stated that he was retaliating for Marichal's having thrown at Wills. He took matters into his own hands as he did not want to risk Koufax being ejected and possibly being suspended for retaliating while the Dodgers were in the middle of a close pennant race.[33] He stated that his throwing close to Marichal's ear was "standard operating procedure", as a form of retribution.[30]

Marichal didn't face the Dodgers again until spring training on April 3, 1966. In his first at bat against Marichal after the incident, Roseboro hit a three-run home run. Later on, Giants General Manager Chub Feeney approached Dodgers General Manager Buzzie Bavasi to attempt to arrange a handshake between Marichal and Roseboro but Roseboro declined the offer.[34]

Dodger fans remained angry with Marichal for several years after the altercation and reacted unfavorably when he was signed by the Dodgers in 1975. By then, however, Roseboro had forgiven Marichal and personally appealed to fans to do the same.[30]

Later career

[edit]The Dodgers went on to win the 1965 National League Pennant by two games over the Giants. Even though the Giants won the two games against the Dodgers during which Marichal had been suspended, the outcome of the season may have been different without the Giants' pitcher's suspension, as he finished the season with a 22-13 win-loss record.[30]

Roseboro once again guided the Dodgers' pitching staff to a league-leading 2.81 earned run average.[35] He caught for two twenty-game winners in 1965 with Koufax winning 26 games, while Don Drysdale won 23 games.[36] In the 1965 World Series against the Minnesota Twins, Roseboro contributed 6 hits including a two-run single to win Game 3 of the series as the Dodgers went on to win the world championship in seven games.[37]

The Dodgers' pitching staff continued to lead the league in earned-run averages in 1966 as they battled with the San Francisco Giants and the Pittsburgh Pirates in a tight pennant race.[38] The Dodgers eventually prevailed to win the National League pennant for a second consecutive year.[39] Roseboro led the league with a career-high 903 putouts and finished second to Joe Torre in fielding percentage to win his second Gold Glove Award.[40][41] The Dodgers would eventually lose the 1966 World Series, getting swept in four games by the Baltimore Orioles.[42]

The following season, after the Dodgers fell to 8th place, Roseboro, Ron Perranoski and Bob Miller were acquired by the Minnesota Twins, which needed a veteran catcher and left-handed reliever, in exchange for Mudcat Grant and Zoilo Versalles on November 28, 1967.[43] While with the Twins, he would be named to his fourth and final All-Star team when he was named as a reserve for the American League in the 1969 All-Star Game.[44]

After the season, Roseboro was released by the Twins. He signed as a free agent with the Washington Senators on December 31, 1969, but appeared in only 46 games for the last place Senators. He played in his final major league game on August 11, 1970 at the age of 37.[11]

Career overall

[edit]In a 14-year major league career, Roseboro played in 1,585 games, accumulating 1,206 hits in 4,847 at bats for a .249 career batting average and an on-base percentage of .326, along with 104 home runs and 548 runs batted in. He had a .989 career fielding percentage as a catcher.[11]

Roseboro caught 112 shutouts during his career, 19th all-time amongst major league catchers.[45] He was the catcher for two of Sandy Koufax's four career no-hitters and caught more than 100 games in 11 of his 14 major league seasons.[11] Baseball historian and sabermetrician Bill James ranked Roseboro 27th all-time among major league catchers.[46]

| Category | G | BA | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | OBP | SLG | OPS | E | FLD% | CS% | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,585 | .249 | 4,847 | 512 | 1,206 | 190 | 44 | 104 | 67 | 56 | 479 | 547 | 677 | .326 | .371 | .775 | 107 | .989 | 42% | [11] |

Television appearances

[edit]Like many Dodgers in the 1960s, Roseboro did some film and television work. He appeared as a plainclothes officer in the 1966 made-for-television film Dragnet. He also appeared as himself in the 1962 film Experiment in Terror, along with teammates Don Drysdale and Wally Moon, and in the 1963 episode of the show Mister Ed called "Leo Durocher Meets Mister Ed."[47]

In the mid-1960s, Chevrolet was one of the sponsors of the Dodgers' radio coverage. When the Los Angeles Dodgers broadcast games on television, Chevrolet commercials were aired in which Roseboro and Drysdale sang the song "See The U.S.A. In Your Chevrolet", made famous by Dinah Shore in the 1950s. Upon seeing the commercials, Dodgers' announcer Jerry Doggett joked that Roseboro's and Drysdale's singing career "was destined to go absolutely nowhere."[48]

Post-baseball career

[edit]After completing his playing career with Washington, Roseboro coached for the Senators (1971) and California Angels (1972–74). Later, he served as a minor league batting instructor (1977) and catching instructor (1987) for the Dodgers. Roseboro and his second wife, Barbara Fouch-Roseboro, also owned a Beverly Hills public relations firm.[49]

In 1978, Roseboro wrote his memoir with writer Bill Libby, titled Glory Days with the Dodgers, and Other Days with Others. In it, he was very direct with his criticism of the baseball establishment and his own shortcomings, as well as those of his teammates, including his one-time roommate and close friend Maury Wills.[50] The book also caused tensions between him and Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley who was reportedly upset by the book; as a result, the Dodgers did not renew Roseboro's contract the following year.[51]

Relationship with Marichal

[edit]After several years of bitterness over their famous altercation, Roseboro and Marichal became friends in the 1980s. Roseboro personally appealed to the Baseball Writers' Association of America not to hold the incident against Marichal after he was passed over for election to the Hall of Fame in his first two years of eligibility. Marichal was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1983, and thanked Roseboro during his induction speech. Roseboro later stated: "There were no hard feelings on my part and I thought if that was made public, people would believe that this was really over with. So I saw him at a Dodger old-timers' game, and we posed for pictures together, and I actually visited him in the Dominican. The next year, he was in the Hall of Fame. Hey, over the years, you learn to forget things."[52]

When Roseboro died, Marichal served as an honorary pallbearer at his funeral. "Johnny's forgiving me was one of the best things that happened in my life," he said, at the service. "I wish I could have had John Roseboro as my catcher."[53][54]

Personal life

[edit]In 1956, Roseboro married Geraldine "Jeri" Fraime. She was a student at Ohio State University and they were introduced to each other by Roseboro's brother Jim.[55] The couple had two daughters, Shelley and Stacy, and adopted a son named Jaime.[56]

After his marriage with Jeri broke down, Roseboro went through financial hardships and contemplated suicide as a result. During this time, he began a relationship with Barbara Walker Fouch whom he credited with saving his life. Roseboro and Fouch married soon afterwards.[57] He also became a father figure to Barbara's daughter from her first marriage, Nikki.[58]

Later in life, Roseboro's health began to fail and he suffered from several strokes, heart ailments, and a bout of prostate cancer.[59][60] He succumbed to heart disease on August 16, 2002, in Los Angeles, California at age 69.[61]

See also

[edit]- List of Gold Glove Award winners at catcher

- List of Major League Baseball career double plays as a catcher leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career games played as a catcher leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career putouts as a catcher leaders

References

[edit]- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

- ^ Stone, Kevin (August 19, 2015). "Juan Marichal clubbed John Roseboro 50 years ago in ugly, iconic incident". ESPN.

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

He was born on May 13, 1933, in Ashland, Ohio, a small town between Cleveland and Columbus where the Roseboros were one of only a few African American families... John Sr. was a chauffeur and auto mechanic who married Cecil Geraldine Lowery when she was 15. She took in laundry and then worked at the J.C. Penney department store. John Jr. was the first of two sons; his brother Jim played halfback for Ohio State in the 1955 Rose Bowl.

- ^ "Meet A Dodger". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. March 1, 1959.

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

After playing freshman football, Roseboro was ineligible for baseball because of poor grades. Brooklyn scout Hugh Alexander spotted him working out with the Central State team, liked his smooth left-handed swing and his strong 5-foot-11, 190-pound frame, and invited him for a tryout when the Dodgers were in Cincinnati.

- ^ a b "John Roseboro Minor League statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1952 Wisconsin State League Batting Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

Brooklyn called Roseboro up in June 1957, shortly after his 24th birthday, because the club needed an emergency first baseman to replace the injured Gil Hodges. Roseboro, who had played first only a few times in the minors, appeared in his first four big-league games at the position.

- ^ "Scouts Rave Over New Campy In Praising John Roseboro". Washington Afro-American. ANP. February 5, 1957.

- ^ Wilks, Ed (March 17, 1959). "John Roseboro Is Learning Fast As Replacement For Roy Campanella". The Day.

- ^ a b c d e f "John Roseboro Career Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1958 All-Star Game Box Score, July 8". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1959 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1959 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1959 World Series - Los Angeles Dodgers over Chicago White Sox (4-2)". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1961 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1961 National League Gold Glove Award winners". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1961 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1961 All-Star Game Box Score, July 11 - Game 1". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ Leahy, pp. 106–109.

- ^ "1962 All-Star Game Box Score, July 10 - Game 1". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1962 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ Leahy, pp. 54–59.

- ^ "1963 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1963 National League Team Pitching Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1963 World Series - Los Angeles Dodgers over New York Yankees (4-0)". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1964 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Catching Better Than 50% of Base Stealers". The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers.

- ^ Mann, Jack (August 30, 1965). "The Battle Of San Francisco". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilstein, Steve (August 22, 1990). "Marichal clubbing of Roseboro an ugly side of baseball". Times-News. AP.

- ^ a b c d e "Book Excerpt: Marichal, Roseboro and the inside story of baseball's nastiest brawl". Sports Illustrated. April 21, 2014.

- ^ Rosengren, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Rosengren, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Bock, Hal (April 4, 1966). "John Roseboro Hammers Homer In First Meeting With Juan Marichal". The Day.

- ^ "1965 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1965 Los Angeles Dodgers Batting, Pitching, & Fielding Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1965 World Series - Los Angeles Dodgers over Minnesota Twins (4-3)". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1966 National League Team Pitching Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1966 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1966 National League Fielding Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1966 National League Gold Glove Award winners". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "1966 World Series - Baltimore Orioles over Los Angeles Dodgers (4-0)". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ Joyce, Dick (November 29, 1967). "L.A. Trades Roseboro to Twins". The Desert Sun. UPI. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ "1969 All-Star Game Box Score, July 23". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Career Shutouts Caught". The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers.

- ^ James, Bill (2001). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. Free Press. p. 392. ISBN 0-684-80697-5.

- ^ "John Roseboro". IMDb. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "On this day... The Dinah Shore Chevy Show premieres". April 20, 2011.

Later, the theme song would be "reinterpreted" by baseball greats Johnny Roseboro and Don Drysdale who recorded commercials aired during televised LA Dodgers games. (FYI, reviews -- not so good...)

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

Barbara gathered up her daughter Nikki and moved to Los Angeles, where she opened a new PR agency and took in John as a partner.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (June 19, 1978). "John Roseboro Sets the Record Straight on his Big League Career". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

One reader was Walter O'Malley. A reporter spied the book on the Dodger owner's desk. "It's terrible," he said. He was "very upset." Roseboro's contract as an instructor was not renewed.

- ^ Rosengren, pp. 169–190.

- ^ Rosengren, pp. 208–210.

- ^ Knapp, Gwenn (August 21, 2005). "40 years later, The Fight resonates in a positive way". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

Soon after he came home, his brother introduced him to Geraldine Fraime, an Ohio State student who became the shy young man's first real girlfriend. "I don't remember proposing," he wrote later, "but maybe I did." When the Dodgers promoted him to Triple-A Montreal in 1956, John and Geraldine married during the season.

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

For Roseboro, the biggest event of 1959 was the birth of his first child, Shelley. He and Jeri later had a second daughter, Stacy, and adopted son Jaime.

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

Barbara Walker Fouch was a long-distance friend he had met in Atlanta, a former model who ran her own public-relations firm. Since she was also going through a divorce, they cried on each other's shoulders in long phone calls... They soon married.

- ^ Rosengren, pp. 175-176, 204.

- ^ "John Roseboro (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

But his health began to fail when he was still in his fifties. Several strokes, prostate cancer, and heart disease led to 51 emergency room visits over 14 years.

- ^ Rosengren, pp. 204–210.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (August 20, 2002). "John Roseboro, a Dodgers Star, Dies at 69". The New York Times.

Book sources

[edit]- Rosengren, John (2014). The Fight of Their Lives: How Juan Marichal and John Roseboro Turned Baseball's Ugliest Brawl into a Story of Forgiveness and Redemption. Lyons Press. ISBN 978-0-7627-8847-7.

- Leahy, Michael (2016). The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-236056-4.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- John Roseboro at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- John Roseboro at IMDb

- John Roseboro at Find a Grave

- 1933 births

- 2002 deaths

- 20th-century African-American sportsmen

- African-American baseball coaches

- African-American baseball players

- American expatriate baseball players in Canada

- American expatriate baseball players in Venezuela

- American League All-Stars

- Baseball players from Ohio

- Brooklyn Dodgers players

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)

- California Angels coaches

- Caribbean Series managers

- Cedar Rapids Raiders players

- Central State Marauders baseball players

- Central State Marauders football players

- Central State University alumni

- Deaths from heart disease

- Gold Glove Award winners

- Great Falls Electrics players

- Leones del Caracas players

- Los Angeles Dodgers players

- Major League Baseball bullpen coaches

- Major League Baseball first base coaches

- Major League Baseball catchers

- Minnesota Twins players

- Minor league baseball coaches

- Military personnel from Ohio

- Montreal Royals players

- National League All-Stars

- People from Ashland, Ohio

- Pueblo Dodgers players

- Sheboygan Indians players

- United States Army reservists

- Washington Senators (1961–1971) coaches

- Washington Senators (1961–1971) players